Why do sovereign wealth funds decide to enter private markets – private equity, real estate, and infrastructure? What are the risks and opportunities they see? In a survey of eight IFSWF members, we found that they tended to allocate to private markets as they believed they could harness a significant return premium over public markets due to the illiquidity of these assets and the fact that the markets are less efficient. Some sovereign wealth funds stated that, due to their long investment horizon (and in some cases, long-dated or non-existent liabilities), they were well suited to bear illiquidity risk.

Other reasons cited for investing in private markets include:

- Private markets provide specific exposures that are impossible or difficult to access in public markets. For example, venture capital provides the opportunity to invest in new innovations in a deeper and richer way than in the public market. Public markets also offer limited opportunities for exposure to infrastructure and real estate. For example, one fund said that real estate investment trusts (REITs), are embryonic in Europe and still developing in Asia. Listed real estate and infrastructure companies also have structural issues that prevent them from providing SWFs with pure exposure to the underlying assets.

- Sovereign wealth funds perceive that private-market investments help diversify their portfolios. However, there is a common view that the diversification benefits may be overstated (and risk may be understated) given that valuations of private markets investments are not marked to market.

- Investment manager performance is seen to be more consistent in certain private markets areas, such as private equity, making it easier to select skilled managers.

But how do sovereign wealth funds go about investing in private markets? What systems and processes do they have to consider? How do they decide on the size of their allocation?

A long process

Most of the surveyed sovereign wealth funds engaged in an extended period of deliberation and analysis before launching their private markets programmes. This process typically lasted for between one to three years, although in one case it was as little as three months. Some funds solicited advice from external consultants or academics to help them evaluate the decision.

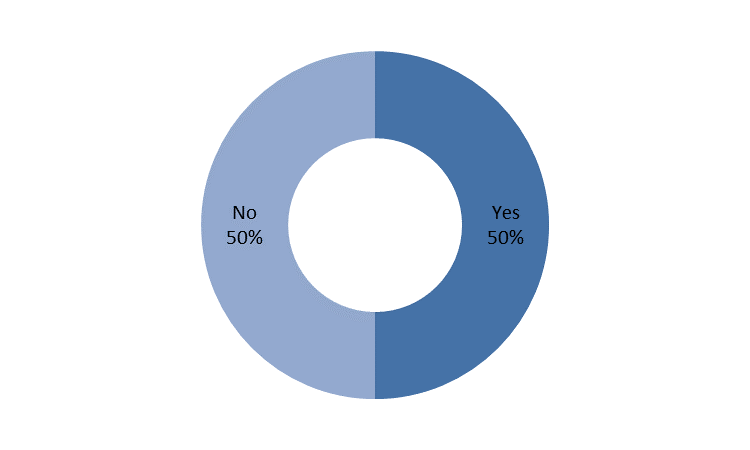

In many cases, sovereign wealth funds needed to overcome stakeholder concerns about whether the premium compensates fully for the illiquidity and other risks associated with private markets investing before launching a private markets programme. Stakeholders generally included boards or government, sovereign funds can also be subject to media scrutiny. Specific concerns and questions raised by stakeholders included:

- whether the fund had the required resources to be successful in private markets

- how it would adapt its organisational structure

- how performance would be evaluated and what benchmark would it use

- whether these investments provided adequate compensation for their complex risks

- the degree of opacity in private markets

- reputational risk.

Exhibit 1: Did you have to overcome concerns from stakeholders of your organisation such as government and/or media to invest in private markets?

Source: IFSWF survey 2016

Sovereign wealth funds had to educate stakeholders on the potential value of private-market investing. In many cases, the funds found real estate easier to explain than private equity and infrastructure. In certain instances, sovereign wealth funds needed to win local support from stakeholders in the investee country, particularly in the case of major real estate projects.

How much to invest in private markets?

Sovereign wealth funds take a wide variety of approaches to determining the appropriate allocation to unlisted assets. On the qualitative side, the most common approach was to clearly define the fund’s objective. One of the sovereign wealth funds we surveyed said that they had “serious doubts about the ability to determine an ‘optimal’ allocation,” as this was determined by the fund’s objectives and what it is trying to achieve, particularly around liability profile. All else equal, liquidity is more of a concern for investors with shorter horizons and more imminent cash needs, like stabilization funds.

Those sovereign wealth funds that have dual objectives of long-horizon capital appreciation and fiscal stabilisation must balance these requirements in their portfolio allocations. “We try to reconcile our ability to withstand a market shock and the liquidity drains that it will impose on us,” said another sovereign fund. “We work out what the minimum level of liquidity and the maximum level of illiquidity can be; this is the same question from a different angle. We watch this number on a weekly basis. We perform that test very frequently.”

Managing the illiquidity in the portfolio is also important because it constrains an investor’s ability to rebalance its portfolio to its desired asset mix after price fluctuations distorts the allocation. “If you are 70/30 and you can’t rebalance when 70 gets to 60, it’s harder to benefit from being a long-term investor. This is how we measure the cost of illiquidity in private assets. We all know that rebalancing is a key component of the total return.” One of the fund we spoke to defines liquidity categories, ranging from A to D, and assigns a rating to each investment. Some of the sovereign funds that receive their funding from natural-resource revenues have seen their liquidity provisions tested over the past year as energy prices have fallen. One such fund said: “Our public portfolio is managed in a very prudent fashion with sufficient liquidity. We didn’t go overboard on direct investment. This has allowed us to manage the current liquidity situation as planned rather than it becoming a crisis. Everything is going smoothly, there are no fire sales.”

Similarly, the illiquidity of unlisted assets and the generally large ticket prices, sovereign wealth funds also need to create guidelines for the minimum and maximum allocations to any region or industry to prevent any unacceptable concentrations in specific sectors or geographies arising in the overall portfolio.

To help set the appropriate allocation some sovereign wealth funds try to quantify the risk of private markets returns. But measuring the standard deviation of private market returns is a complicated exercise. According to one sovereign wealth fund, volatility can be higher than anticipated after de-smoothing the returns to adjust for the lags in valuations and adjusting for leverage. The fund believed that “for US real estate, these adjustments can push the volatility into double digits”. “Risk is trickier than returns,” said another. Most sovereign wealth funds we surveyed agreed that risk management in private markets is largely a qualitative exercise. “We manage risk through diversification, transaction structure and governance. But quantifying the risk using data analysis doesn’t seem to lead to meaningful conclusions,” said the same fund. “We’re constantly thinking about risk, trying to manage it downwards using transparency, access, governance control, and oversight to manage the risks.” Consequently, risk management is often a manual exercise: One fund recalled sending an analyst around their offices with a spreadsheet to capture the sector exposure of each of its private investments.

Which private assets to choose?

Another key decision is to which private-market segments should any fund allocate. While they all share some similarities, they also have key differences. One fund points out that while these investments might be amalgamated under one department, they need to be managed separately as each sector has its own drivers and expected returns and risks. Investment duration also differs. Infrastructure investments have a seven-to-15-year cycle, while real estate is shorter with five-to-10-year investment horizons, says one fund. “We are puzzled by this move of combining real estate and infrastructure in a single asset class. We tend to think that the risks, drivers, the ways that the markets organise themselves, and the way you access them, are all quite different. You have to be aware of those differences and nuances. You want to have participants in each market rather than trying to bring them both into the same asset class.”

Another difference between the different segments is their cash yield and their ability to provide a hedge against inflation risk. Real estate and infrastructure are seen more as fixed income replacements, with the potential to hedge against inflation risk over longer periods. Some sovereign funds have increased their allocation to these segments as fixed-income yields have fallen to historic lows. Private equity, in contrast, is perceived to be more of a return-enhancing growth driver.

Tooling up to invest in unlisted assets

To maximise the benefits of investing in private markets, sovereign wealth funds need to put the right team in place. Investing in private markets also requires different skills and expertise to investing in public markets. These capabilities need to be built up, regardless of the strategy used to deploy capital. Initially sovereign funds need to establish dedicated risk management teams to develop processes and procedures to limit and manage risks relating to excessive leverage of assets, reputation, taxation and regulatory changes, as well as currency fluctuations.

However, it is important to know how to choose the managers or partners. In the words of one investor, “Investing in private markets is like flying a plane. You cannot get out mid-flight, so you really need to know the type of plane you are boarding”. You also need to trust who you are flying it with. Professor Josh Lerner believes that manager selection is key. “In all private markets, there is huge disparity between good managers and not-so-good managers. The returns to choosing good managers are really quite high.”

To assess private equity and real estate managers, sovereign wealth funds have developed a range of tools and processes. “We run background checks on deals, organisations and individuals,” said one fund. Another produces a scorecard to evaluate each manager’s people, process, and capabilities. The fund monitors the scorecard over time, assigning managers a green, orange, or red light. Another approach our research revealed is having opportunities evaluated by two independent teams to provide a second opinion.

As part of manager selection, sovereign wealth funds also must consider the relatively high fees that managers charge in private markets. “This is a topic of enormous interest for LPs [limited partners, or investors in private equity funds] around the world. And it is reasonable to see why,” said Lerner. “There are a variety of responses. One is shadow capital: separate accounts where LPs commit more assets in exchange for more favourable economics.” He says that – even over the last five years – fees have become more variable due to investors bargaining harder with their managers. So-called side letters may mean that one investor may have much more favourable terms to another.

Lerner also observes that some sovereign funds are deciding to forego paying high fees to develop internal private equity or real estate expertise to invest alone or alongside private-sector partners. He says there’s “a lot of interest in direct investing [among sovereign wealth funds]. It is appealing and has potential for large cost savings. But direct investing is considerably harder than first meets the eye.” Sovereign wealth funds can struggle to attract and retain talent in their private markets teams and implement plans to develop and retain key staff in these areas.

Hiring the right team is vital to success in private markets investing, particularly as performance can be difficult to measure as unlisted assets are not marked to market, and, consequently, reported valuations have a lag time. To optimise the benefits of investing in unlisted assets, the team must know when to enter an asset, or choosing canny managers, to reduce the risk of capital loss. But investing in private markets “doesn’t mean you can buy anything,” said one fund. “To benefit from being a long-term investor [in private markets], you have to make sure that your assets will survive an economic cycle.” Professor Lerner agrees, “there is a tendency for investors to jump in at the wrong times,” he says, “to invest at market peaks. In all private markets, this is the worst possible strategy! These markets tend to exhibit a ‘boom-bust’ dynamic with tremendous variation in performance across vintage years.”

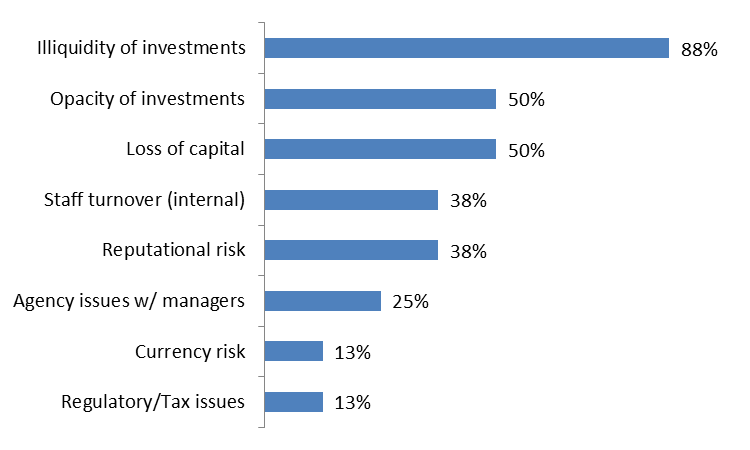

Exhibit 2: What are some of the major risks that your fund saw in private market investments at the time the decision was made to enter these markets?*

* Chart shows percentage of SWFs that explicitly identified each risk as a major consideration. Source: IFSWF.

Evaluating performance

To estimate expected returns, sovereign wealth funds often use a building block approach. They start with the risk-free rate (which is currently very low in most developed economies) and then add in one or more risk premia. For example, one fund expects private equity to generate a two-to-three per cent illiquidity premium over public equity over a seven-to-ten-year period with an appropriate level of risk. Another approach is to define a fixed hurdle rate of return as well as a benchmark market index. “For infrastructure, we have a real return objective of 5.5 per cent as well as a passive performance benchmark of infrastructure stocks,” said one fund. “We would ideally like to beat both of these benchmarks. If you’re going private you need to be earning a return premium relative to passive stock exposure.” A third fund set a return hurdle that was linked to inflation: the benchmark is the inflation rate in the G7 countries plus a premium of four per cent.

To evaluate performance, sovereign wealth funds rely on a range of benchmarks. Some funds may evaluate any given commingled fund against a group of its peers investing in similar assets. Another approach is to assess the entire portfolio against the private markets portfolio of a universe of endowments or foundations. “It has to be tailored,” said one SWF. “You can’t compare your venture capital performance to an overall private markets number and reach meaningful conclusions.” Compared to public markets, where benchmarks are ubiquitous, there are few benchmarks for private markets investments. Even within private markets, the number of available benchmarks varies: there are more private-equity than infrastructure benchmarks, for example.

“There are relatively few benchmarks and there are big differences across the benchmarks,” says Lerner. “One approach that I recommend to SWFs and other investors is to have a ‘big tent’ approach with multiple indicators of market activity. One may look better than the other, but looking at multiple benchmarks will give you the best overall sense of how well you are doing.”

Deploying capital

Of course, once the target allocation to private markets is determined, the team is in place and the measure of success determined, the SWF must then identify opportunities and begin to deploy capital. “Deploying money in the private markets takes time,” said one sovereign fund. “Each year we think through deployment pacing, distributions, and capital calls. Mean-variance analysis concludes that you need much greater exposure to private markets, but in reality we are constrained by the need to not blunder in blindly. If we decided tomorrow that we wanted to allocate 35 per cent of the portfolio to private equity, which is where some university endowments are, we couldn’t get there responsibly in two, three, or even five years. The biggest challenge is deploying capital and keeping pace while the fund is growing.” A few sovereign wealth funds also talked about the importance of making acquisitions at a balanced pace to ensure the private equity portfolio was appropriately diversified across vintage years.